On Sept. 25, 1957, Eagle Scout Ernest Green Jr. and eight other African-American students walked through the front doors of Little Rock’s Central High School and onto the pages of history. Their simple action capped off months of planning, weeks of legal battles, a handful of street-level skirmishes, and a high-stakes showdown between the governor of Arkansas and the president of the United States.

On Sept. 25, 1957, Eagle Scout Ernest Green Jr. and eight other African-American students walked through the front doors of Little Rock’s Central High School and onto the pages of history. Their simple action capped off months of planning, weeks of legal battles, a handful of street-level skirmishes, and a high-stakes showdown between the governor of Arkansas and the president of the United States.

Few had expected the integration of Central High to be quite so eventful. In the wake of Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court case that outlawed segregation in public schools, three Arkansas school districts had already quietly integrated.

What’s more, says Green, “the University of Arkansas had admitted a few years before a small number of black students to the law school and the med school. The library in Little Rock had desegregated quietly. The bus system had desegregated without a lot of problems. So our expectation was this was an agreed-upon process with the school board and the courts and that it, too, would be fairly quiet.”

But something had changed in 1956. A primary challenge from segregationist Jim Johnson had pushed first-term governor Orval Faubus, a moderate by Arkansas standards, far to the right. When a poll showed 85 percent of the state’s voters opposed integration, Faubus declared “no school district will be forced to mix the races as long as I am governor.”

Changing, But Slowly

Despite Faubus’ pledge and growing white anger, the Little Rock School Board continued plans to obey court orders and integrate its schools — albeit with “the least amount of integration over the longest possible period,” according to the district’s six-year plan. In spring 1957, the 500 or so black students who lived in Central’s attendance area were invited to apply for admission that fall. About 80 did so, including Green, then a junior at Horace Mann High School. At the time, he was thinking as much about his own future as he was his place in history.

“Central had a reputation for being one of the best high schools in the region — not just in Little Rock, but in the whole mid-South area,” he says. “This would be a big help for me to get into college.”

But he also knew someone had to step forward to help turn the Brown decision into a reality.

“I didn’t have this extended vision that this was going to change options for lots of people later on, but I did see it as an opportunity to try to make the ’54 [Supreme Court] decision come alive,” he says.

Over the summer, Superintendent Virgil Blossom winnowed the list of applicants to 17 and held interviews with them and their parents. Green’s father, Ernest Sr., had died a few years earlier, but his mother, Lothaire, was fully on board. A lifelong educator, she had been among those who fought for equal pay for black teachers in 1943. (The Greens had even helped house legendary attorney Thurgood Marshall, who handled the equal-pay case for the NAACP and was not welcome in Little Rock’s segregated hotels.)

By the end of August, eight of the 17 students left the group, in part because Blossom told them they couldn’t participate in any extracurricular activities at Central. That left nine willing students: Green, Minnijean Brown, Elizabeth Eckford, Thelma Mothershed, Melba Pattillo, Gloria Ray, Terrence Roberts, Jefferson Thomas and Carlotta Walls. Green was the only senior (although he was the same age as the juniors because

he had skipped first grade).

Not Running Away

On Sept. 2, the day before school was set to open, Gov. Faub

us called out 300 members of the Arkansas National Guard to keep the Little Rock Nine out of Central. Two days later, the students showed up anyway. Because of a miscommunication, student Eckford arrived alone at the wrong end of the school, where an angry mob shouted curses at and spat on her — all while the guardsmen watched.

Finally, a white integrationist named Grace Lorch escorted Eckford to safety. The other students didn’t fare much better. They also retreated, taking shelter at the home of Daisy Bates, president of the Arkansas NAACP, where they would spend the next three weeks trying to keep up with their schoolwork.

The chaos of that day only strengthened Green’s determination to enter Central.

“I didn’t know the governor, but I figured if he had to call out 200 or 300 members of the Arkansas National Guard to keep me out of school that there was something behind those walls that I ought to be pursuing and not running away from,” he says.

After the Sept. 4 standoff, the U.S. Justice Department requested an injunction against the governor’s use of guardsmen to keep Central segregated. District Judge Ronald Davies heard the case Friday, Sept. 20; among those testifying were Green and Eckford. Davies immediately granted the injunction, and Faubus withdrew the guardsmen.

On Monday, Sept. 23, the day after Green’s 16th birthday, Little Rock police officers whisked the Little Rock Nine into Central for the first time, though the students didn’t stay until the final bell. When the mob learned they were inside, they viciously attacked four black journalists and threatened to storm the school. Assistant Police Chief Gene Smith sneaked the students out of the school and past protestors who were screaming racial slurs.

Emerging Signs of Hope

Shaken by the situation, city officials asked President Eisenhower to send federal troops to restore order. By the end of Tuesday, nearly 900 members of the 101st Airborne were on the ground in Little Rock. At 9:22 a.m. the next day, they escorted the Little Rock Nine through the front doors of Central High, rifles in hand and bayonets fixed.

The worst of the crisis had passed, but the next eight months didn’t pass without incident. Outsiders called in at least 43 bomb threats, the African-American students faced daily harassment and the white students who tried to befriend them were ostracized. Still, there were signs of hope. Like when two white seniors helped Green in physics class throughout the year, perhaps protected by their status as athletes and by the fact that troublemakers typically didn’t enroll in challenging science classes.

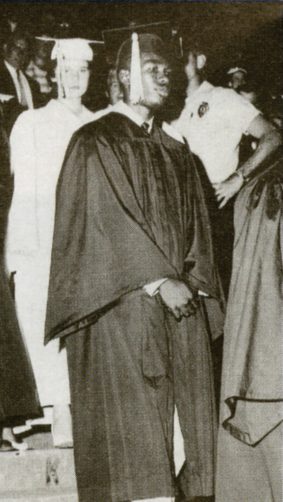

Finally, on May 27, 1958, Green became the first African-American to graduate from Central High School. Among those looking on were Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and two platoons of federalized National Guardsmen.

Finally, on May 27, 1958, Green became the first African-American to graduate from Central High School. Among those looking on were Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and two platoons of federalized National Guardsmen.

As Green crossed the stage and received his diploma, few — if any — of his classmates applauded. Sixty years later, the applause is unending.

Shining On

After graduating from Central High School, Ernest Green enrolled at Michigan State University, where he continued working for civil rights. He earned a bachelor’s degree in social science in 1962 and a master’s degree in sociology two years later.

During the 1960s and ’70s, Green directed the A. Phillip Randolph Education Fund before joining the Carter administration as assistant secretary of labor for employment and training. Since leaving government service in 1981, he has worked as a consultant in private industry; he currently works with Matrix Advisory, an institutional asset manager.

Throughout his career, Green has worked to improve educational opportunities for minorities. He has chaired the Historically Black Colleges and Universities Capital Financing Advisory Board and served on the boards of Quality Education for Minorities Network, Fisk University and Clark Atlanta University.

Hundreds of organizations have honored him, including the Urban League, the NAACP, and many colleges and universities.

But one honor stands above: In 1999, President Bill Clinton presented him and the other members of the Little Rock Nine with the Congressional Gold Medal. At a White House ceremony marking the occasion, Clinton remembered how pervasive segregation was in his home state in the 1950s — and how some brave students did what was right.

“It was just the way things were. It was unfortunate, but that’s the way things were,” Clinton said. “And all of a sudden, [the Nine] showed up, and it wasn’t the way things were anymore.”

From Scouting to the Schoolhouse

Ernest Green became an Eagle Scout on Nov. 30, 1956, and he recalls being only the third or fourth African-American in Little Rock to reach Scouting’s highest rank. His Scoutmaster, Louis Bronson, was a neighbor, the grandfather of one of his closest friends and something of a surrogate father after Green’s father died.

“My dad passed when I was 13, so being around a group of men and boys who seemed to have

positive goals was an important activity for me,” he says.

There’s no merit badge for making history, but Green says Scouting helped prepare him for what happened at Central.

“Scouting teaches you how to handle challenges and not get overwhelmed completely by them,”

he says. “I think that was an important part of my being able to navigate that year.”

Scouting also taught him bravery. Throughout that pivotal year, he embodied these words from his Handbook for Boys: “You know the ideals of the Scout Oath or Promise. You know right from wrong, and in spite of urging and ‘wise cracks,’ you can be brave in the face of danger, and brave in the face of temptation.”

Throughout his career, Green has been a supporter of Scouting. He received the Silver Beaver while serving as assistant secretary of labor in the Carter administration and received the Distinguished Eagle Scout Award in 1995. More recently, he served as honorary chair of the BSA’s 100th Anniversary National Hall of Leadership.

“I have nothing but positive things to say about Boy Scouting,” he says. “As I move toward retirement, I’m not as active as I was, but I still regard Boy Scouts as a very important development item in my life.”

Inspire Leadership, Foster Values: Donate to Scouting

When you give to Scouting, you are making it possible for young people to have extraordinary opportunities that will allow them to embrace their true potential and become the remarkable individuals they are destined to be.

Donate Today

This is positive news to overcome the challenges of segregation of a school. And to start a new chapter of integration in the life of a school and it’s students. Well done.